with a tetrodotoxin-bearing newt, Taricha granulosa

The adventure to become a toxinologist

I heard about the International Society on Toxinology (IST) for the first time in 1964, when I was a student of biology and biochemistry at the Goethe-University in Frankfurt, Germany, working part time at the Institute of Legal Medicine. The head of the toxicology lab, H.W. Raudonat, was one of the first members of that Society. He worked on snake venoms and needed help collecting venom from cobras, which he kept in the basement of the Pharmacology Institute. It was indeed a risky venture, that nonetheless sparked my interest in venomous and poisonous animals.

However, my career in toxinology started with a big bang: I was bitten, not by one of the cobras, but by a Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum! For $100, I had bought that specimen from Ross Allen´s Reptile Institute in Silver Springs, Florida, and kept it at home in a simple terrarium to collect its venom. At one of these occasions, the reptile turned around and bit the back of my right hand. It caused a dramatic effect. I passed out for a couple of minutes due to a rapid drop of blood pressure. Fortunately, my mother was around and called the ambulance, which rushed me to the University Hospital, where I spent a week recovering. To my dismay, H. suspectum had been transferred to the zoo in the meantime. Nevertheless, this event didn´t stop me from continuing to work on snake venoms in preparation for a doctoral thesis.

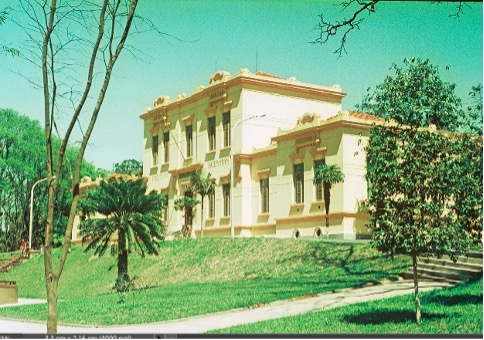

In January 1966, I read an announcement of a Symposium on Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins to be held at the Butantan Institute (Fig. 1) in São Paulo, Brazil, the “Mecca” of snake venom research! I applied to the Volkswagen Foundation for a student fellowship to attend the meeting and to study snake venoms at Butantan for five months. Luckily, my application was successful and on the first of July, I flew to São Paulo; a 24-year-old student, first time overseas, far from home!

When I arrived at the institute, I was welcomed by Wolfgang Bücherl, who had arranged my stay and later gave a course on venomous animals. He introduced me to the members of the Biochemistry Lab, where Fajga Mandelbaum and Mina Fichman took care of me during the following months (Fig. 2).

Fajga taught me how to fractionate snake venoms (Sephadex was the “wonder matrix” at that time) and to analyse venom enzymes. With Mina, I tested the kallikrein activity of various venoms on the guinea pig ileum preparation, including that from Heloderma suspectum (I had bought the venom from Bill Haast´s Miami Serpentarium), by assaying the release of bradykinin from blood plasma. To learn more about that, I went 350 km inland to Ribeirão Preto to visit Mauricio Rocha e Silva, head of the University’s Department of Pharmacology, the “king” of kinin-research. In his lab, I had a chance to test Heloderma venom on dogs. When injected i.v., it caused a dramatic drop of blood pressure (confirming my own experience). Before I returned to São Paulo, Mauricio invited me to come back after doctorate, a great honour for a young student.

The Symposium was held in the lecture hall of the Butantan Institute from July 17 to 23, 1966. It was my first experience attending a scientific meeting and listening to presentations of the famous toxinologists I knew from the literature. I also got the chance to present a short paper on my biochemical studies on Heloderma venom. This event and the months I spent in the biochemistry lab of Butantan convinced me that toxinology was the field to strive for.

Back home, I continued to work on my thesis on snake venoms and finally received my PhD in August 1968.

When J. Gerchow, the director of the Institute of Legal Medicine, offered me a position in the toxicology lab, I hesitated. Brazil was still on my mind, but forensic science is an interesting field as well. Finally, I accepted his offer, which I never regretted. During my entire forensic career spanning over 40 years in academia (I was appointed professor in 1985), I dealt with people from all walks of life, including perpetrators and victims as well as patients intoxicated with alcohol, drugs etc., a challenge, I would have missed by doing pure research only. Nevertheless, venoms, poisons and toxins from animals and plants were the main subjects of my scientific research activities.

In 1969, C.C. Yang (Taiwan) published the first amino acid sequence of a snake venom toxin, cobrotoxin from Naja n. atra (C.C. Yang et al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 188, 65, 1969). In the same year, I isolated a-bungarotoxin from the venom of the Chinese krait, Bungarus multicinctus. In disc-electrophoresis, the toxin exhibited a single band and, as I assumed, should be a candidate for sequencing studies. Then the question arose as to where that could be done. Why not go overseas?

During the Brazilian Symposium, I had met Tomoji Suzuki from the Institute of Protein Research in Osaka, Japan, and was much impressed by his presentation on snake venom analyses. I wrote him a letter to explore the possibility of analysing the toxin’s primary structure in his institute. I received a positive answer and I applied to the German Research Foundation (DFG) for a research fellowship, which was granted.

On December 1, 1970, I arrived in Osaka and was greeted by Sadaaki Iwanaga, who took care of me during the next six months. At the Institute, work began the following day and then six days a week, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. It was an exciting time, and I learned a lot, performing manual Edman-degradation and amino acid analysis of the peptides after fragmentation of a-bungarotoxin. In close cooperation with the colleagues of the lab (Fig. 3), we finally completed the amino acid sequence of the toxin within four months. Consisting of 74 amino acid residues and five disulfide bridges, it was the largest venom neurotoxin at that time! (D. Mebs et al., Hoppe-Seyler´s Z. Physiol. Chem. 353, 243, 1972)

Besides my forensic work, toxinology and IST became an important part of my academic career. I attended almost all IST-World Congresses and IST Section Meetings and I felt very honoured when I was elected Secretary-Treasurer in 1982, finally serving the Society for 26 years. It was most rewarding, because it provided me with opportunities such as making contacts or forming alliances with colleagues in the field of toxinology. With many of them, a life-long friendship developed.

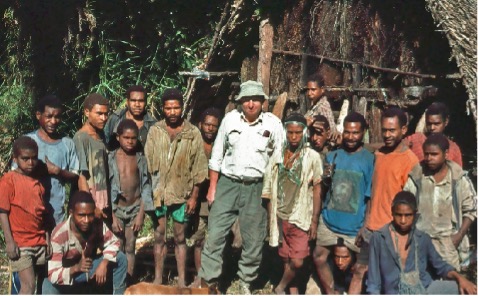

My research subjects included venomous and poisonous marine as well as terrestrial animals. Nobuo Tamiya from Sendai, Japan, who worked on sea snake venoms, visited our lab in 1965 and told me, the young student: “Be aware: the best part of our work is collecting the specimens we like to study!” I kept this in mind and always enjoyed exploring the coral reefs of the tropical seas, the deserts and the rainforests in search of the unknown. I still remember one of the highlights, when I joined the expedition of Jack Dumbacher from Chicago in 1994, who was searching for poisonous birds in Papua New Guinea (Fig. 4). I owe a lot to my wife Hannelore, who took care of the kids while I was away and with good reasons worried about my safe return.

Becoming older, time takes its toll. Many of my friends and colleagues have passed away, like Cassian Bon, John Daly, Frank Gubensek, Ernst Habermann, Gerd Habermehl, Alan Harvey, Sadaaki Iwanaga, Elazar Kochva, Fajga Mandelbaum, Zwonimir Maretic, Akira Ohsaka, Phil Rosenberg, Fin Russell, Alistair Reid, Nobuo Tamiya, just to name a few. I still do some studies on newts, caterpillars, butterflies etc. with support of my former colleagues of the lab. But time moves on. Last but not least, I am happy and grateful that I was able to witness the steady growth of a new field of science, toxinology.

Correspondence: mebs at em.uni-frankfurt.de